On September 12, 2010, tears glistened in Lady Gaga’s eyes as she accepted the highly coveted Video of the Year award at the MTV Video Music Awards.

“Thank you so much. I love my fans so much. All my little monsters watching. Tonight, little monsters, we’re the cool kids at the party.”

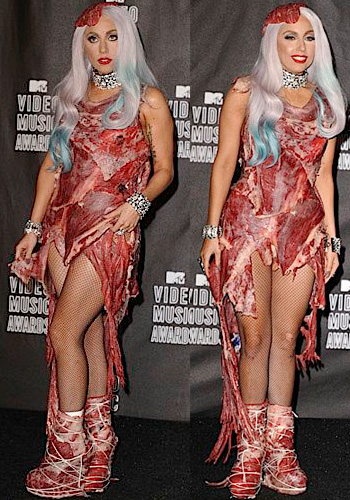

If you’re like I am, the immediate thought was, “Little monsters? Really?” That kind a rhetoric is only slightly more distracting than Lady Gaga’s outrageous wardrobe choices (which, don’t get me wrong, I love by the way. You work that meat dress, girl!)

I didn’t think a lot about the use of the word “monster” until the release of Kanye West’s highly anticipated post-Taylor Swift Gate album My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. Returning from a self-imposed (and probably well-deserved) exile, Kanye West came right out and directly addressed his pariah status. (After all, Yeezy isn’t one to beat around the bush.) In his new single, aptly titled “Monster,” Kanye raps, “Gossip, Gossip n—-r just stop it/ Everybody know I’m a motherf—king monster.”)

I realized then, that monsters are all around us, literally in pop culture and figuratively within us. A significant part of the artistic narrative is dealing with, and being scared by, the monsters that plague us both in society and within ourselves. So what happens when people stop trying to be what society makes them and let their inner monster roar?

Incredible art, that’s what.

Let’s take a look at these pop culture monsters and attempt to figure out their appeal and why monsters act the way they do. I have divided this topic into three segments—after all, monsters come in pretty big proportions. This series will deconstruct monster roles in society using Beowulf, Kanye West, and Where the Wild Things Are as central examples.

Part One: Grendel, an original gangsta (er…monster)

About ten years ago, a much more self conscious and impressionable me sat in my eleventh grade AP English Composition class, waiting for the bell to ring so I could go to my locker and get a snack.

We were reading Beowulf that week. Though my teacher tried to make it interesting and accessible to a room of 16 and 17-year-olds, we were just far less interested in Old English heroic epic poems and significantly more interested in how they could sneak vodka from their parent’s liquor cabinets without being noticed. To say the least, it was sort of an exercise in futility.

One thing does stick out, however: The discussion of the monster Grendel, and why he was the way he was.

Grendel, as we learn, is a horrific, miserable monster who lives in the swamp with the other bannished monsters and sinners. He was created from the spirit of Cain. Yes, Cain and Abel, an Old Testament story about a man who kills his brother out of spite after God rejects his offerings. Cain committed the worst thing imaginable, which beyond murder in the Christian tradition, is to murder your own kin.

Upon further reading, one wonders if Grendel’s exile is not one of his own personal doing, but rather somehow a case of mistaken identity, more like guilt by association. Why exactly he is down there with all the evil monsters? Did he himself really ever do anything wrong? The story never seems to directly address that. I can’t decipher a smoking gun that caused God to put him with the other monsters and spirits.

Beowulf, hero of the Geats, comes to the aid of King Hrothgar of Danes, after he gets word of an evil monster named Grendel terrorizing the kingdom. Beowulf promises to rid the downtrodden Danes of all their monster troubles and restore their kingdom of peace and happiness. The Danes accept Beowulf and his men with open arms, and they throw a big party in the hall to celebrate the impending conclusion of all their troubles.

Apparently, slaying monsters takes adequate pre-gaming. Beowulf and company spend all night drinking and having fun, singing the praises of God.

Grendel resents his status as a social pariah, and the sound of Beowulf and the other Danes singing the praises of God pushes him over the edge. They’re having fun. He’s not. And, to top it off, they’re singing the praises of God, the one who put him in exile in the first place.

(Oh no, they didn’t!)

After all, God is the one who banished him to his place of misery and exile in the first place. Grendel waits until the men go to sleep, then attacks them, taking thirty men back to his cave to munch on.

I reminded more of cantankerous neighbors who call the police on a good house party than a truly evil being. You could say that maybe Grendel was just hungry, but I think it’s a case of extreme emotional eating.

Yes, Grendel does horrible things. He stalks and eats Danes. But at the same time, he kind of got a bum deal. Like Cain and Abel, his misfortunes don’t justify his killings—obviously, killing innocent people is wrong. But is Grendel just a self-fulfilling prophesy? He is expected to act like a monster, and in response he lives up to other people’s expectations when maybe all he wanted was just to be invited to the party.

Naturally, Beowulf saves the day, a heroic act that sets the tone of salvation for the rest of the story. He defeats Grendel in hand to hand combat by tearing off Grendel’s arm. It is a mortal wound, and Grendel, consumed by now physical as well as emotional pain, retreats back to his liar to die, and eventually drowns himself in the swamp because the pain is too great.

So, what did we learn from Grendel? Monsters are lonely, and normally act the way they do out of spite and frustration. People expect them to antagonize because that is the role they’re deliberately destined to play. Monsters terrorize and heckle, but at the end of the day, they eventually self-destruct.

Sound familiar at all? It’s not a huge cry from the way a lot of culturally polarizing celebrities act, and in the context of this essay, I’m using Kanye West as an example.

You were wondering how I was going to transition from Beowulf to Yeezy, weren’t you?

Which brings me to…

Kanye West, the Media’s Monster, Prophet, and Pariah

When thinking of an example of a modern day Grendel, I couldn’t help but turn my attention to Kanye West, especially a song entitled “Monster” featuring Rick Ross, Jay-Z, and Nicki Minaj. (I need to warn you that the video has both explicit images and language. I mean, my mom might read this someday.)

The American Media makes certain people out to be monsters, and, like many iconoclasts, Kanye is only too eager to live up to his reputation. For example, anybody remember Kanye’s post-Hurricane Katrina claim that “George Bush doesn’t care about black people,” not to mention his hijacking of the MTV Video Music Awards, aka Taylor Swift-gate? If only we could forget. It was all over the tabloids for weeks.

The media casts him as a monster, and Kanye isn’t the type to back down from a challenge. In this song particularly, he simultaneously embraces and rejects his monster status.

This song accurately speaks to a duality of monster living: It’s as limiting as it is liberating. Acting like a monster can be a powerful high because you live unapologetically on your own terms, but the comedown is never pretty. Speaking your mind comes with a cost—it alienates the people around you, and at the end of the night you have no one to share your successes with.

Like Grendel in Beowulf, is Kanye West just a lonely monster, acting out for attention by living up to his reputation? I don’t believe the two are that dissimilar.

There are many instances of the song I could reference as Kanye wearing his monster status like a badge of honor, but I think the chorus is the most context rich.

Gossip gossip/

N-ggas just stop it/

Everybody know I’m a muthaf-cking monster/

I’ma need to see your f-cking hands at the concert/

I’ma need to see your f-cking hands at the concert/

Profit profit, n-gga I got it/

Everybody know I’m a muthaf-cking monster/

Kanye not only claims his monster status, he celebrates it. As if to say, “Haters, are you new here? I’ve always spoken my mind. I’ll be your King of Controversy as long as people keep buying my records and coming to my shows.”

I refer to the line: Profit, profit, n-gga I got it. Sounds a little like “prophet, prophet.” I believe it’s a double-entrendre. History shows us a long line of prophets that are as widely scrutinized as they are respected. In the music world, Kanye is simultaneously prophet and pariah, loved for his art but rejected for his egomania.

Because who’s really making out like a bandit at the end of the day? Kanye or the haters? Kanye is selling records not only because of the success of his art but for his notoriety as well. When one more person is reached by his music, for the right or wrong initial reasons, that person is changed. Meanwhile, someone’s got to get paid for that record sale. Guess who? That’s right—Kanye.

So what did we learn here? Kanye West, like Grendel in Beowulf, acts out like a monster because of his loneliness even though it comes with monetary success Yes, he has notoriety and platinum records, but lacks any meaningful emotional intimacy which eventually leads to a cycle of destructive behavior.

And now, some very, very sad Monsters–Where the Wild Things Are

To say that I cried when I first saw this movie in theaters would be understatement, because my reaction was less of a cry and more like the uncontrollable bawling of a 7-year-old who just found out that Santa Claus isn’t real. I had never cried that much in a family movie, with the exception of E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial when I was five. (I’m almost positive if you didn’t cry in E.T., you have no soul.)

For those of you that haven’t seen the movie, spoiler alert. Where The Wild Things Are follows the adventures of Max, a disobedient yet sensitive young boy who runs away from home to escape the desperate controllings of his mother. He sails away in a boat and crash lands on an island that houses fantastical monsters who display shockingly real human emotions. They make him their king, but their close knit group eventually falls apart and Max feels it is best if he leaves and goes back to the human world.

I remember driving home with my boyfriend, mascara stained tears streaking down my face.

“So, what the hell was that movie getting at?” I remarked indignantly. “You try to do the right thing by building a cohesive, loving family, and when it doesn’t work out, you just leave?” The thought was extremely unsettling to me. Tony listened patiently while trying to talk me down from the edge of my near hysteria.

In WTWTA, Spike Jonze creates a rich, whimsical tapestry punctuated by unanswered questions. I’m not the first to point out that the film is allegorical, simultaneously representing Max’s strained relationship with his mother while helping the monsters build an inevitably doomed utopia.

We find the monsters in the midst of crisis. K.W., a cornerstone member of the group, has abruptly left to pursue her relationship with other friends, abandoning the remaining monsters and throwing them into disorganized in-fighting. The monsters initially want to eat Max upon meeting him, but after hearing his completely fabricated tall tales of conquest they collectively decide to turn to him for leadership to bring the group back from near implosion.

“You were their king, and you made everything right?” Carol, a heavily conflicted monster, asks.

“Well, yeah,” Max tentatively replies.

“Well, you know, what about loneliness?” Carol asks.

“What he’s saying is,” chimes in Douglas, another monster, “Will you keep out all the sadness?”

The monsters look at him with pleading looks of desperation. Max tells them what they want to hear, that he has an invincible sadness shield that will keep away all the sadness. The monsters accept him readily as their king, built on Max’s runaway lies. They celebrate the dawning of Max’s reign by running into the forest, hooting and howling in a wild rumpus. They are a curiously assembled band of misfits, but it seems as if the dark days are over under Max’s reign and their reunited makeshift family.

Again, monsters are lonely. The storyline of Where the Wild Things Are doesn’t entail how the monsters get there, but something tells me it could be a similar situation to the one of Grendel in Beowulf—maybe they’re there by no fault of their own, a sequence of unfortunate circumstances, perhaps.

Their eagerness to eat him is overridden by their palpable sadness. Max tells the monsters of tall tales in which he defeated monsters bigger than they are, and they believe him because they’re looking for answers. History tells us that marginalized people will flock to charismatic leaders and false prophets in their desperation. This is no exception.

Monsters often express themselves in extreme ways. Each character in WTWTA represents a hyperbole of human emotion. Douglas is rational. Carol is irrational. Alexander is a coward. Judith is a pessimist. Carol’s outbursts are always precipitated by hurt feelings, most of the time caused in unintentional ways. Whenever he becomes upset, he destroys his home, the symbolic structure of family, in his rage because he can’t deal with reality falling so short of his expectations. We might feel that Carol’s actions are rash and destructive, but the audience sympathizes with his frustration. Everybody has been let down in their lives—the monsters we see on screen just have a more obvious way of showing it.

Later, after the last of Carol’s outburst in which Max is exposed not as a king, but a child, K.W. and Carol have a blow out fight. After Carol storms away, K.W. Reacts by saying, “Can you believe him?

Max responds, “He doesn’t mean to be that way, K.W. He’s just scared.”

K.W. Says, “He just makes it harder, and it’s hard enough already.”

Max: “He loves you, you’re his family.”

K.W.: “Yeah,” she pauses. “It’s hard being family.”

Have you ever noticed that sometimes you treat the people who are closer to you worse than you would treat a stranger? Unless you’re some sort of saint, you’re probably guilty of it. We fight with our mothers, our fathers, our spouses, our brothers and sisters not because we’re bad people, but because of some ironic twist of human nature. If a stranger on the street insulted me, I would think he’s extremely rude and messed up, but it wouldn’t hurt me like if a family member insulted me instead. It’s because we actually care about what people close to us think of us.

This movie has a lot of crazy symbolism that I could point out, but for the sake of length and my own truncated attention span, I’m going to stop it here.

So, in conclusion, what have we learned from these monsters, Grendel from Beowulf, Kanye West, and Where the Wild Things Are?

Monsters are complicated beings who act irrationally because they’re most often lonely and conflicted. If we come full circle in this essay and think back to Lady Gaga and her album The Fame Monster, we are invited to think not about the monsters within us, but to beware the monsters around us: superficial fame that consumes us, bad relationships that drain us, and immoral people looking to take advantage of us.

Society creates monsters so people can feel morally vanquished at the end of the day. Without monsters, there could be no good because there could be no evil. The trick, however, is to be able to decipher what people’s intentions really are. That is, who in reality is just a misunderstood friend, and who, at the end of the day, is a real monster.

Leave a Comment